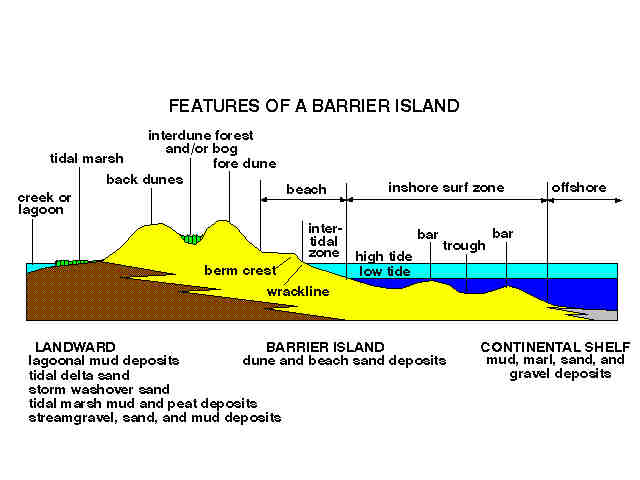

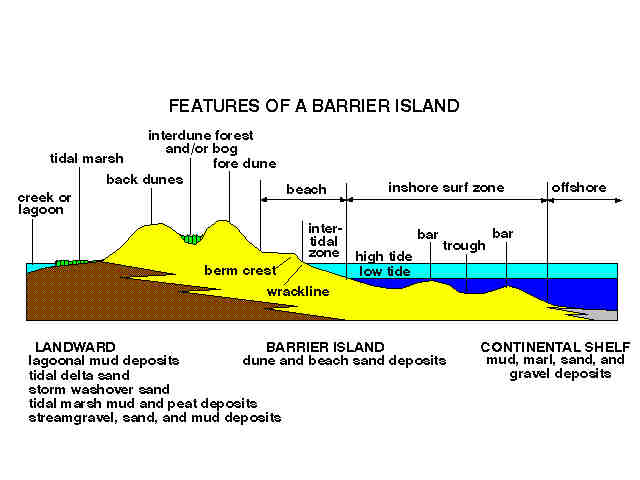

The berm is the crest of the beach, generally above the average high tide line. The berm represents a general break in slope, above which wave energy reaches only during highest tides in combination with storms. The berm separates the intertidal zone from a generally barren stretch of dry sand and the first dunes. This dry, storm-deposited beach sand is the source of sand for dunes in the back beach area. The surface of the back beach generally becomes littered by the lighter debris blown shoreward from the intertidal zone mixed with materials left behind from storm surges.

The back beach area is only flooded during winter storms and during the highest spring tide surges. These events may leave massive amounts of debris piled in the flat back beach area (called "flotsom" and "jetsom"). Winter coastal winds dry out the back beach area and redistribute some of the sand to the back beach dunes. Back beach dunes frequently reach 20 to 30 feet in elevation in undisturbed localities, and may take several decades to centuries to form. In the past dunes were commonly sacrificed to add sand to beaches and to allow coastal residents a better view. The foolishness of removing dunes is illustrated by a simple evaluation of property damages after a winter storm or hurricane in areas where the dunes have been removed!

Similarly, the building of groins and jetties help to trap sand moving with the long shore current. These structures trap sand and benefit the residents on the up- current side of the groin. Unfortunately, the down current side of a groin is then shut off from long shore sediment supply and is subject to erosion, often severe erosion as illustrated by the beachfront community of Westhampton Beach on Long Island!

The western-most groin on Westhampton Beach up-current from the devastation zone caused by several nor'easters of the early 1990's. Storm waves and tidal surges demolished as many as 300 residences down current of a excessive groin field constructed by the U.S. Army, Corp of Engineers. The shut off of the longshore sand supply guaranteed the community's destruction.

Beaches are constantly changing from season to season and year to year. Each year the spits on the end of barrier islands grow longer. Eventually a storm will come along and strip much of the sand away and deposit it on offshore bars or onto the shore of the next island down current. As sea level continues to rise the barrier islands migrate landward. In the New York area is is quite common to find fossils of organisms that inhabited land and back bay and lagoonal environments washing up on the beach. This suggests that the barrier islands have moved landward through time, allowing wave energy to erode the older shore deposits that are now offshore. In regions where tectonic forces are causing the land to slowly rise old beach and barrier islands are left stranded, forming inland ridges parallel to shore. When sand supply increases islands grow, when it is reduced islands erode. The variability of sand supply in the past was a reflection of climate and whether sea level was rising or falling. When the glaciers were rapidly melting huge amounts of sand were contributed to regional shorelines. However, as the sand supply dindled as the glacier receeded, and sea level continued to rise older barrier islands vanished. Sand ridges on the continental shelf are, in part, the eroded remnant of submerged barrier complexes.

The modern barriers are quite transient. Historical reports demonstrate that the shoreline has migrated in the order of several miles in some locations along the Atlantic Coast since colonial times. Islands that once existed offshore have vanished. One example in the New York Bight area is Hog Island, a small island that existed off the coast from Rockaway, Queens, NY. It vanished after a hurricane in 1893 (NY Times 3/18/97, p. B1). Other islands existed offshore from Coney Island. These islands were,in-part,demolished by the activities of early settlers disrupted the shore dunes with heavy grazing and cut down the cedar forests in the back beach areas. However, one good hurricane or strong nor'easter can drastically change the coast in one event, with or without the aid of human activity. Evidence for vanished islands along the coast of the New York Bight comes from the occurrence of Indian and colonial artifacts, bones, and the pickled stumps of cedar that frequently wash up on area beaches.

Anyone who spends time beachcombing will note that more gravel and shell material will accumulate on the upper intertidal zone on the beach when wave energy is low (when local wind energy is low). When the wind is strong the shoreface tends to be covered with a blanket of sand, and gravel and shell material is transported seaward. In general, I find that if there is a breeze greater than 10 miles an hour there is no point in going to the beach to collect artifacts, shells, or fossils.

Return to the

New York Bight Home Page

Return to the

New York Bight Home Page

Phil Stoffer and Paula

Messina

CUNY, Earth & Environmental Science, Ph.D. Program

Hunter College, Department of Geography

Brooklyn College, Department of Geology

In cooperation with

Gateway National Recreational Area

U.S. National Park Service

Copyright May, 1996

(All rights reserved; use as an educational resource

encouraged.)>